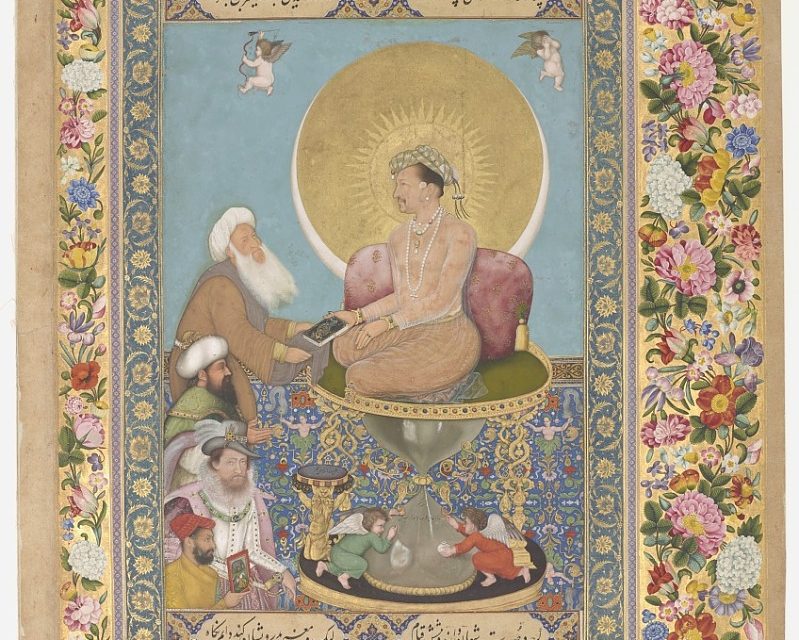

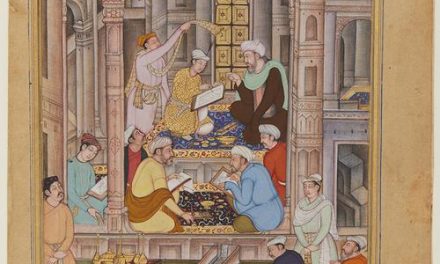

Mughal allegorical portraits, uplifting and grandiloquent in tone, were conceived as divine manifestations of the emperor. Designed to provide the monarch with an indulgent and flattering image of himself, the allegorical paintings depicted the emperor accomplishing brilliant and heroic exploits, prevailing over his harshest enemies, and receiving divine inspiration. To attain this objective, the Mughal painters adapted European symbols and allegories and painted an all-powerful monarch steeped in grandeur yet suffering the ineluctable decline of his physical strength.

No attempts were made to present Emperor Abu’l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar or simply known as Akbar as the divine ruler and no divine attributes appear to be linked with Akbar’s portraits during his reign. The European symbols depicted in some of his portraits are later additions that are mostly posthumous portraits. Allegorical portraits became very popular during the reign of Akbar’s son Nur-ud-din Muhammad Salim or popularly known as Jahangir. Jahangir had made every effort to impress his courtiers and subjects with his wealth and power. The portraits were also an effort to convince Jahangir to himself of his Mughal superiority. “Before 1615, Jahangir’s painters usually presented the emperor in a narrative context; but after that time he is often shown as a majestic figure isolated with symbols of wealth and power. These changes, which deliberately glorify Jahangir, reflect the increasingly sacral character of the Mughal emperor. Symbolic portraits made for Jahangir often had a decidedly human dimension: they revealed the emperor’s hopes and sometimes, his fears; and they frequently referred to specific historical events.”[i] The allegorical portraits belonging to Shah Jahan’s reign were balder statements of imperial power in comparison to the state portraits. Shah Jahan’s love and passion for grand imagery led to the depictions of his life and court being transformed into visions of cosmic splendor.

Discussed below are some of the most popular and common allegorical symbols seen in Mughal miniature paintings:

- NIMBUS/HALO

The nimbus or the halo has been a popular symbol or divinity since the early forms of Indian art. Percy Brown says that the halo was seen for the first time in the sculptures of the Gandhara school of art as haloes of different kinds adorned the head of the Gautama Buddha. It is popularly depicted as a circular disk. “Buddhism having thus appropriated the saintly circle, it was carried with the art of that creed to all the distant countries which accepted the doctrine of the Great Teacher. In India a later and Hinduized form of Buddhism, the Mahayana, then took over the symbol, from which it was only a step to the Brahmanical art of medieval times, so that it appears in the sculptures of that country from then onwards, as an attribute of many of the Indian divinities.”[ii] This symbol travelled to Europe in the fifth century. Though halo was at first sparingly used by European painters, it gradually went on to become an accepted symbol of the Byzantine Church and was henceforth used profusely in all figurative art. The religion of Islam, did not identify with the use of symbols except those of its own making. The halo was first seen in the manuscripts of the Abbasid rulers who commissioned the making of these manuscripts to Greek painters, who in turn had copied from the Byzantine illustrated books which they used as their guide books to learn about the style and technique. The painters of the Timurid and Safavid school of art did not adopt the halo as a symbol in their compositions. In some paintings of the holy family of Islam or the saints, a golden flame was used to denote divinity. The halo was popularly painted by painters of the West. Christian art adopted the symbol to such an extent that the halo was regarded by many scholars as a symbol of purely Christian meaning and symbol. The halo travelled back to the land of its origin with the coming of the Jesuit missionaries to the Mughal court. Jahangir encouraged the use of the symbol as an excellent method for distinguishing the Mughal emperor from the other people in a composition. He was a firm believer of the divinity of emperors and rulers. The use of the halo was strictly restricted to the ruling sovereign of the empire and in the portraits of the members of the royal family. “The idea of its use in this connexion was entirely Jahangir’s, so that it is found in no likeness of his predecessors painted previous to his own reign; any such portraits which included this appendage have been executed subsequent to Jahangir’s orders on this subject. A rare exception, however, would be any early portrait of his ancestors to which a nimbus had been added by a later hand.”[iii] Figures of Hindu and Muslim saints were depicted with their heads ringed with a plain gold halo. Gradually, rulers of dynasties like the Adil Shah of Bijapur adopted the symbol in their portraits as well.

- CHERUBS

The cherubs were another popular symbol that the painters of the royal atelier adopted in the allegorical portraits. “The introduction of winged cherubs in pictorial art is an oriental feature and has a history of its own: but the employment of cherubs of the renaissance type for decorative purposes-even when the faces and figures are somewhat orientalized-is a characteristic for which the Jesuit influences may reasonably be held responsible.”[iv] Cherubs represent the second order of the ninefold celestial hierarchy. Very often, cherubs are confused with putto. Putto (plural putti) were representations of a naked child especially a cherub or a cupid on Renaissance art. Amina Okada states that the putti usually bore emblems of imperial sovereignty.

- CROSS

One of the oldest and most universal symbols adopted by the Mughal painters was the cross. The cross was considered the perfect symbol of Jesus Christ since it depicted His sacrifice upon the sacrifice. The cross became the symbol of Christianity, the symbol of atonement, salvation and redemption through Christianity.

- CROWN

The crown which is usually seen in the hands of the putti descending from clouds, is a symbol of royalty and victory.

- GLOBE

The globe is a symbol of power. It is frequently shown as an attribute of God the Father in Christian art. In the hand s of Christ, the globe is an emblem of His sovereignty. In the hands of a man, the globe is a symbol of imperial dignity. The Mughal emperors were often showed standing on a globe or holding an orb in their hand.

- ANIMALS

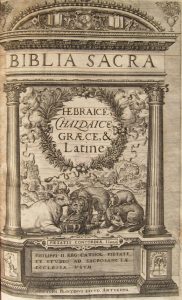

Almost all allegorical portraits depict a lion and a lamb seated peacefully together under the emperor’s feet or seated on a globe under the feet of the emperors to express universal aspirations of the dynasty. The depiction of these animals was symbolic of the Messianic rule. Ebba Koch discusses this in the context of the famous Royal Polygot Bible. The first page of the Bible depicts an ox, a lion, a lamb and a wolf, seated peacefully together within an architectural frame.

This was prophesized by Isaiah as follows:

“The wolf lies with the lamb,

The panther lies down with the kid,

Calf and lion cub feed together

With a little boy to lead them.

The cow and the bear make friends,

Their young lie together.

The lion eats straw like the ox.

The infant plays the cobra’s hole;

Into the viper’s lair

The young child puts his hand.

They do not hurt me, no harm,

On all my holy mountain,

For the country is filled with the knowledge of Yahweh

As the waters swell the sea. (Isaiah 11: 6-9)”[v]

Ebba Koch further discusses how the depiction of these animals together was also symbolic of the union of nations in the Christian faith and the languages in which the Old Testament appears in the Bible. [vi] Koch says that the Mughal painters did not have any hesitancy in adapting to the use of the animals in their compositions as animals enacting a particular event in a landscape was one of the oldest pictorial traditions in Islamic painting.

During Jahangir’s reign, a lion associated with sheep, goats or oxen became a popular symbol for peace guaranteed by the just rule of Jahangir.

The above symbols can be noticed in several Mughal miniature paintings and it is interesting to see how these symbols were adopted by the Mughal emperors to project their proximity with God. The application of the allegorical symbols added an element of spirituality to the artist’s work and elevated the status of the emperor to that of a divine figure.

Text References:

[i] Zeenut Ziad, ed., The Magnificent Mughals (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002), 174, 175.

[ii] Percy Brown, Indian Painting under the Mughals: A.D. 1550 to A.D. 1750(New York: Hacker, 1975), 172.

[iii] Ibid., 174.

[iv] Edward Maclagan, The Jesuits and the Great Mogul (New York: Vintage Books, 1932), 256.

[v] Ebba Koch, Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology: Collected Essays (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001), 2.

[vi] Ibid

Image courtesy:

Jahangir preferring a Sufi Sheikh to Kings, St.Petersburg Album, Bichitr

Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper, circa 1615-1618

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.

Recent Comments