The Mughal Atelier

The Mughal emperor Akbar’s regime saw a major shift of the method & materials used in paintings followed from the pre- Mughal times. The painters in the pre- Mughal times passed on their knowledge of art on to their own family, preferably sons or of a near or even distant family. However, all that changed in Akbar’s regime and a modified apprenticeship was applied to teach paintings. The painting workshops were more complex in their organization than any other atelier witnessed in India.

The Mughal atelier was home to some eminent painters whose paintings are housed in some of the most extraordinary museums and some exclusive private collections today.

EMINENT PAINTERS OF THE ROYAL ATELIER

‘Abd As-Samad

The great Iranian painter was a painter at the court of Shah Tahmasp. He later entered into the service of emperor Humayun at Kabul in 1549 and he was also active at the court of Emperor Akbar during the time period of circa 1556-1600. He went on to teach other well known painters of the atelier like Daswanth and Bizhad. ‘Abd as-Samad played an instrumental role in the genesis of the Mughal school of painting. Known as Khwaja ‘Abd as Samad Shirin Qalam, the artist supervised the work on the Hamzanama manuscript in circa 1560 and saw it to completion. Working with indigenous artists, the extraordinary artist and his students incorporated both the pre-Mughal and the Persian style of painting that was eventually synthesized in the Mughal school of miniature painting. He never accepted the spatial and material realism promoted by Akbar and thus remained a largely ceremonial adornment of the Mughal court. “The Ain-i Akbari refers to ‘Abd as-Samad as follows: “Khwaja ‘Abd as Samad-styled ‘shirin qalam’, or sweet pen. He comes from Shiraz. Though he had learnt the before he was made a grandee of the court, his majesty which caused him to turn from that which is form to that which is spirit. From the instructions they received, the Khwaja’s pupils became masters.”i

Aqa Riza

Aqa Riza was active at the court of Mirza Muhammad –Hakim and later entered the service of Jahangir in circa 1588. Aqa Riza’s works show him to have been a controlled, precise painter, making carefully balanced, highly decorative compositions. Yet Aqa Riza remained conservative, and deeply indebted to his training in Iran; figures seldom take on real individuality. “Aqa Riza favoured the Iranian refine decorative approach over Akbar’s earthy naturalism and so won favour with the young Prince Salim. A major work from the Allahabad years is the Anvar-i Suhayli (Lights of Canopus, British Library), to which the artist contributed five signed paintings, dated circa 1604-1605.”ii He was one of the major artists working at the court of Jahangir and therefore his style was enormously influential on the development of the young Jahangir’s taste.

Abu’l Hasan

Abu’l Hasan, son of Aqa Riza, was active at the court of Jahangir between circa 1600-1630. He quickly surpassed his father in skill and in imperial esteem. Abu’l Hasan was lauded above all other artists by Jahangir, who also awarded him the title ‘Nadiruzzaman’ or ‘Zenith of the World’ in circa 1618. The figures painted by Abu’l Hasan have a weight and density that coupled with his extraordinary perception of personality traits that convince the viewer of both the reality and the individuality of the figures being depicted by the painter. This naturalism was found in one of the earliest works of the painter, a page from the Anvar-i Suhayli (Lights of Canopus, British Library) of circa 1604-1610. “Abu’l Hasan’s heyday was in the last decade of Jahangir’s reign. His picture appear prominently in collected works recording the celebrations of Jahangir’s accession, painted a decade after the event but incorporating portraits of contemporary personalities of the court, many identifiable through inscriptions in earlier portrait studies. Abu’l Hasan quickly emerged as the emperor’s favoured portraitist. He was engaged by Jahangir to portray the emperor in a series of allegorical portraits. With the regime change in 1627, Abu’l Hasan ceased to be active. He was closely identified with the personality and patronage of Jahangir and so did not find favour when Shah Jahan succeeded, although one imperial portrait indicates this decline was not immediate.”iii

Basawan

Basawan was one of the foremost painters was active at the court of Akbar during circa 1565 to circa 1598. He figured prominently in nearly every important manuscript that was illustrated in the royal atelier during his tenure at the Mughal court. “Basawan’s most lasting legacy is the response to European art that he brought to Mughal painting. His ability to grasp the pictorial possibilities of both atmospheric and linear perspective was unmatched. His paintings of the later 1590s are a revolutionary fusion of these European pictorial devices into a newly emerging post-Safavid Mughal style. Like all imperial painters of his time, he had access at the court to northern European engravings of Christian subjects and cameo-type portraits, and he drew freely on that imagery. Basawan typically places his European-inspired figure in a visionary Mughal setting with fantastic rock formations of Iranian derivation.” ivHe showed an extraordinary receptiveness to European art, and incorporated many of its visual effects-especially pronounced tonal modelling and atmospheric perspective into his works in circa 1560s. Basawan combined these new techniques with his compositions, portrait-like faces and many empirical observations of typically Mughal characters and settings and thus charted the course of Mughal painting away from its Persian roots.

Bishandas

Bishandas was active at the court of prince Salim between circa 1600-1604. He was later sent to the court of Shah Abbas by emperor. He is one of the five painters mentioned frequently by name in the memoirs of Jahangir. He was the only Mughal painter who had travelled outside the Mughal court, to Persia and left some impact of his work in the foreign land.

Farukkh Beg

Jahangir’s most idiosyncratic painters, Farrukh Beg also known as Farukkh Husayn was one of the few Mughal painters who received great patronage from the Mughal emperors. Farukkh Beg was active at the court of Mirza Muhammad-Hakim in early 1580s, at the court of Akbar between circa 1590-1609 and at the court of Jahangir between circa 1609-1619. In 1585, while serving in the royal atelier of Akbar, the title of ‘Farrukh Beg’ was conferred upon him according to the Akbarnama. Farrukh Beg contributed to the Baburnama (circa 1589) and the first illustrated edition of the Akbarnama (circa 1589–90). Farukkh Beg was one of the greatest of all artists working in the royal atelier of the Mughal empire. He proved that a painter could maintain a personal artistic identity even in the midst of his changing physical circumstance and patronage alliances changed. He never accepted the spatial and material realism promoted by Akbar and thus quickly moved from the Mughal court to render his services in the court of Bijapur.

Keshav Das

Keshav Das also known as Kesu Das, Kesu Gujarati, Kesu Kahar, Kesu Kalam and Khurd, worked for both Akbar (till around circa 1570-1570) and Jahangir (till around circa 1599- 1604). He was ranked fifth in a list of seventeen best painters of the royal atelier by Abu’l Fazal the historian and biographer of Akbar. His contributions to the major Akbar manuscripts between circa 1580-1590 showed his conservative nature as an artist. “He was a prolific and versatile painter who was known for his copies and adaptations of European engravings.” v

Manohar

Manohar, son of Basawan, worked at the court of Akbar (during circa 1582-1600) and Jahangir (during circa 1600-1604). Manohar surpassed other artists of the Mughal atelier by making the most in his patrimony and native talents. He began painting in the 1580s, but it was a decade later before his style was fully formed. He made well known contributions to the finest manuscripts commissioned to the atelier during this time at the court. He often derived his inspiration from European engravings and prints. He absorbed techniques of natural modelling and pictorial space, which he tempered with strong colours and surface rhythms. “Manohar gives three-dimensional substance to his figures, and to his contemporaries they must have had astonishing presence. And this is one aspect of the imperial tradition that Jahangir continues after his accession demanding an even greater intensity of observation from his artists.”vi

Mansur

Mansur was active at the Mughal court between circa 1600-1604 and at the imperial painting workshops between circa 1589-1600 and circa 1604-1626. His career was centered on the reign of Jahangir, whose interest in natural history became the mature artist’s focus. He entered Jahangir’s court when the latter was still a prince. Mansur came to maturity as a painter during Jahangir’s reign. Mansur is mentioned very frequently in the memoirs of Jahangir. Like most of Mansur’s works throughout his career, “it is a more coloured drawing than a painting; areas of unpainted paper-which serve to place emphasis on the colour-are prominent, and there is only a minimal layering of pigment. The lines are minute, and painstakingly applied, absolutely different from the swift vitality and independent rhythms typical of Iranian line. Mansur worked with great deliberation, to both accurately describe visual traits, and to pleasingly balance the various elements of the work. The surface brilliance (of the colour, for example) coupled with the acute observation, is a perfect balance of naturalistic and formal concerns-and is thereby typical of the Jahangiri style.”vii He received the highest accolade from Jahangir with the title of ‘Nadir al-Asr’ or ‘Wonder of the Age’. This honour was bestowed upon him for his sheer ability to paint and preserve the likeness of the animals and flowers that engaged the emperor’s attention.

Text References:

i Abu’l Fazl ‘Allami, trans. H.Blochmann, ‘Ain-i Akbari (Calcutta: 1939-1949), 114, 554, 582.

ii Emperors album, 71

iii Milo Cleveland Beach, The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hassan and Some English Sources for his style. From emperors album, 73

iv ibid, 42

v Milo Cleveland Beach et al., Masters of Indian Painting (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2015), 160.

vi Milo Cleveland Beach, The Grand Mogul Imperial painting in India 1600-1660 (Massachusetts: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1978), 25.

Image courtesy:

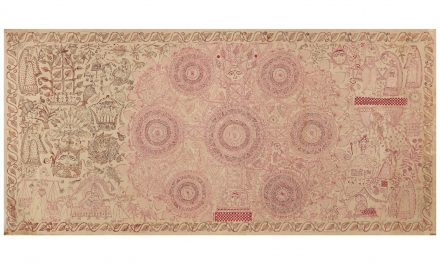

Title: A COURT ATELIER, FOLIO FROM A MANUSCRIPT OF THE ETHICS OF NASIR (AKHLAQ-I NASIRI)

Date: circa 1590 – 1595

Artist attribution: Sanju

Medium and technique: Opaque watercolour, ink and gold on paper

Provenance: Aga Khan Museum

Wow ! what imense knowledge about mughal art